Friday, May 17, 2013

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Critically speaking, Black is still Beautiful

–Lekan Balogun–

–Lekan Balogun–

Black people have come a long way—through the murky terrain of the ignominious trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, to ‘myths’ and stereotypical images, which denigrated their humanity. But, that ‘black’ spirit has not been broken. With artistic ingenuity, they transformed abuse into creativity, imitation into invention, signifying abuse into firm and acceptable worthy identity. From syncretism of faith, wherein Orisha seizes upon the Catholic strictures and subsumes Western denigrating faith into a worthy identity through Lucumi, Candombles, Santeria etc, to the dramatic arena — Black Theatre — that draws heavily from indigenous forms and cultural traditions, articulating people’s needs and aspirations, that are not only magical but also constructive, to music such as Blues, Reggae and Calypso, Black people continue to demonstrate the sheer magic of resilience for which they are “notoriously” famed.

The roll call is a long one. Blacks, who defied odds, at least from the artistic perspective and set worthy examples and in whose footsteps Edaoto is passionately and vigorously following—such tradition of commitment to culture and time-hallowed tradition. Clarence Muse provides a vivid example. He notes the Black American playwrights’ doggedness, and the determination and the sheer astuteness of the Black Self in asserting its presence on the American White dominated stage. He writes that “our aim was (is) to give vent to our talent and to prove to everybody who was willing to look, to watch, to listen, that we were as good at drama as anybody else had been or could be. The door was opened a thin bit to us and, as always, the black man, when faced with an open door, no matter how small the wedge might be, eased in”. Shange also clearly exposes the American stage as an agent of colonialism by challenging—actually manipulating the minstrelsy in favour of Black consciousness and personality. By putting on black faces for a musical show, Whites conceal the fact of dramatizing their own anxieties, rather foisting that sense; naked sense even, of their inferiority on Blacks, writes Cronacher. But, with spell #7,Shange’s theatrical militancy or what Tejumola Olaniyan describes as “combat aesthetics” is re-energized and refocused as she has done earlier in for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, engaging the racial and gender questions as they affect African-Americans, whether male or female and, through the play, dislodges the complex historical effects of differences and White racist constructions of the Black people. Such commitment is the hallmark of Harlem writers, poets and musicians—some kind of black theatre, literature and music that Imamu Amiri Baraka insists should be acts of liberation.

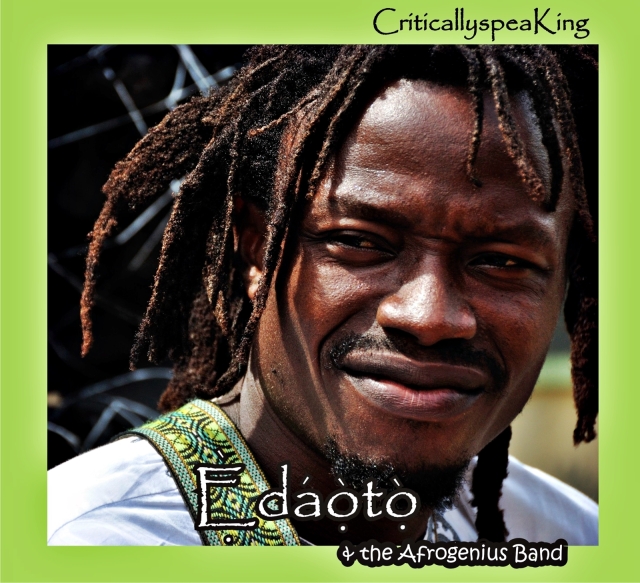

Recently the truth of that statement was re-echoed at the Alliance Francaise (French Cultural Centre), Yaba, Lagos amidst sweat and excitement, aesthetic fervor and sated satisfaction expressed by the guests gathered at the launch of “CriticallyspeaKing”, Edaoto’s nine tracks offering of music and African philosophy. The young and dynamic, highly gifted artiste continues to play that role serving as the “conscience” of the society’s cultural mind, breaking the barriers of culture and norms created by the huge and imposing presence of foreign values promoted by the dual machinery of Western education and religion. Much reminiscent of veteran performers like Hugh Masekela, the South African duo of Mariam Makeba and Brenda Fassie of blessed memory and of course Femi Kuti, the young Edaoto and his Afrogenius Band express a deep sense of what it means to be Black and at the same time to be creatively effervescent, despite stifling condition of living created by the antagonistic classes in the country who, rather than see to the welfare of the populace, engage in political meanderings and permutations.

From the political engagement of ‘Stand Up’, which passes scathing remarks at the seeming lethargy of freedom fighters and, the docility of the masses towards sociopolitical situation of the society calling instead for collective action against oppressive state machinery, which perpetuates corruption and disregard for the dignity and survival of the common populace; to ‘Kajowapo’ wherein the love of a woman is metaphorically played out and translated, given more engaging purpose in ‘Had I?’, as love of country, of root and race stemming from belief in oneself and the past of one’s ancestry; to the call and response of ‘Maromikiri’, infused with scintillating guitar, saxophone and rattle percussion, which is no less deeply philosophical as ‘Aye O f’eni f’oro’ that takes one through a mystical journey into the soul, the nature of man and familiar yet strangely slippery terrain of human relationship mired by deceit, treachery and disappointment, calling instead for thoughtfulness and counsel derived mainly from the power and spirit within. Ritual thought sourced from myth mixes freely with aesthetic vibrancy of folk tradition that recalls the skill and artistry of Tunji Oyelana, Jimi Solanke, Orlando Julius Ekemode and Akeeb Kareem, the Blackman’s signature virtuoso performances; ‘Somi Edumare’ foregrounds the indispensability of the Divine in human affairs, through invocation which ordinarily translates into a renewal of some sort, a connection with the cosmos and essence of being through prayers while ‘Blackman’ advocates racial identity and can best be summed up in Tejumola Olaniyan’s description of such as a worthy attempt at “race retrieval” and “cultural self-apprehension”, concluding an energetic philosophical offering.

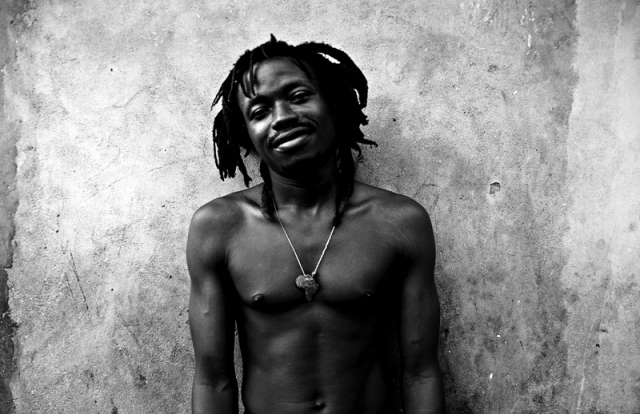

Listening to “Criticallyspeaking”, one could argue that the Black spirit and Black Revolution have been given a boost, albeit, by an expression of commitment by a young artiste whose society today is riddled with imbalance and loss of value. As Ron Karenga notes, “For all art that does not contribute to and support the Black Revolution is invalid, no matter how many lines and spaces are produced in proportion and symmetry and no matter how many sounds are boxed in and blown out and called music”. Lawrence Agbeniyi is a metaphor, and, as Edaoto—the Unique Being—he transforms wearing the toga of the traditional griot, the travelling minstrel who embodies the vitality of the oral art form, and at the same time, the garb of the intellectual in whose hands music becomes the ideal veritable tool to engage in a soul-searching, a quest for the collective to embrace the necessity and the naturalness of the Black humanity, whose true essence has remained intact, untainted, in spite of many years of abuse, denigration and, in some cases, self-delusion.

Works Cited

Coleman, Michael. “What is Black Theater? Interview with Imamu Amiri Baraka”, Black World, 20,

1971,p 338.

Cronacher, Karen. “Unmasking the Minstrel Mask’s Black Magic in Ntozake Shange’s spell #7’, in Feminist Theatre and Theory. Kayssar, Helene,(Ed) London: Macmillan Press Limited, 1996.

Karenga, Ron “Black Cultural Nationalism”, in The Black Aesthetics, Addison Gayle (Ed). New York: Doubleday: Anchor,1972, p31

Muse, Clarence. In Sampson, Henry T. Ghost Walks: A Chronological History of Blacks in Show

Business, 1865–1910. Scarecrow Press, Incorporated, 1988.

Olaniyan, Tejumola. Scars of Conquest/Masks of Resistance: The Invention of Cultural Identities in Africa, African-American and Caribbean Drama. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth Century America. New York: Oxford UP, 1974.

Wintz,D Cary. Black Culture and the Harlem Renaissance. Houston: Rice University Press, 1988.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)